The European Commission is expected to publish its proposal for the European Health Preparedness and Response Authority (HERA) in the coming days. This new structure will be part of the European Health Union package to strengthen Europe’s capacity to respond to cross-border health threats. Announcing the initiative earlier this year, Stella Kyriakides, EU Commissioner for Health and Food Safety, said that “COVID-19 has revealed gaps in [EU] collective preparedness and response. HERA is a fundamental part of the solution that we need for the next health crisis to prepare better and respond more swiftly, together.”

Indeed, the COVID-19 pandemic has reminded us how damaging it can be to lose sight of the public interest and the principles of equality while dealing with deadly health emergencies. We got to face a two-track pandemic fuelled by vaccine inequity across the world. While people in richer countries are about to receive a third dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, large portions of the poor countries struggle with providing their essential workers and populations at risk with at least the first dose.

As the Health Commissioner said, the pandemic revealed gaps in the EU health emergency response system, and HERA is to be the missing part. However, in order to succeed public health and equitable global access to medical countermeasures should be placed front and centre. Otherwise, we risk it being just a lot of hot air.

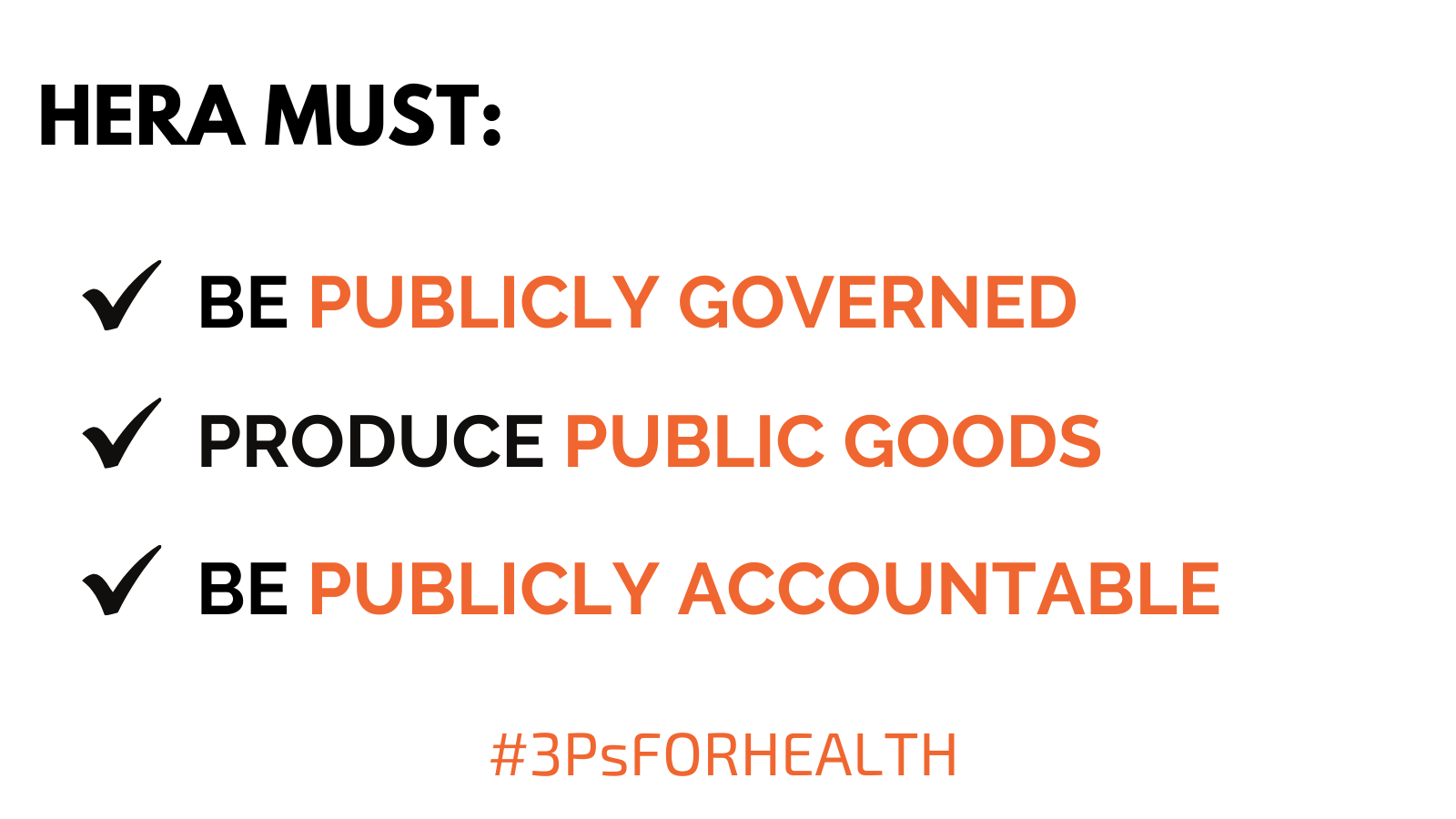

HERA will shape the way the EU prepares for the next potential health crisis, so it needs to be done properly. When designing HERA, the European Commission must meet three minimum conditions – the 3Ps – to avoid repeating old mistakes, wasting public resources, and endangering public health.

The only guarantee of HERA’s independence, autonomy, and integrity is public governance. Relying on independent and evidence-driven foresight and science, HERA has to make decisions aligned with the public interest and global health needs. Public governance will ensure synergies and cooperation between HERA and other EU and national public health authorities and agencies, such as but not limited to ECDC, EMA, and US BARDA. Being publicly governed means considering the health industry an important stakeholder and partner, but not giving it the right to decide on priorities.

Contributing to global and equitable access to medical countermeasures should be another condition for HERA. The use of public resources has to be reflected in return on public investment and in positive health impact. All end products of HERA have to be affordable, available, and accessible to people globally in case of health emergency. For this to happen, HERA must consider its results public goods and attach access conditionalities and open science principles to funding agreements.

Finally, with its unique and responsible role in the EU health preparedness ecosystem, HERA must remain publicly accountable. It will cope with the significant risks of failure, negotiating with powerful partners, acting quickly, and managing a large budget. To succeed it has to adopt high transparency standards at all levels and act in an inclusive way. In order to generate trust and legitimacy, HERA needs to work closely and consult regularly with a range of public health interest organisations, patients, consumers, payers, and researchers. As a standard practice, HERA should disclose COIs declarations, publish in a timely manner annual work plans and activity reports, budgets, R&D agendas, research and product pipeline, minutes of meetings, lists of experts.

HERA may fail while trying to protect EU citizens and people around the world from a health crisis. But it will be unforgivable if it failed because the EU lost sight of public health interest again.